Change in An Unexpected Place

By Maggie Thach Morshed

This piece was a finalist in our Fall 2016 Essay Contest; it takes place in Seoraksan National Park, in South Korea.

Image courtesy of the author.

To get to this spot—where this 48-foot bronze Buddha statue welcomes me to Sinhuengsa Temple—a plane flew me over the Atlantic, a subway zipped me through Seoul, a bus weaved me through the winding roads of Gangwon province, and all of it delivered me here.

Since I picked up my life in Nevada and moved to South Korea seven months ago, change has been my siren song. It was what I needed. Change has been the driving invisible force in my life, and I’m excited to see it actually manifest in front of my eyes. What I feel will be reflected in what I see.

It’s the end of September, and the leaves on the trees in Seoraksan National Park should be in the midst of transformation. The pictures I saw online assured me this was the place to see summer turn into autumn. In the photos, the mountains looked engulfed in flames. When I arrive, Seoraksan is cloaked in darkness. But when I wake up in my pension room, I can see that the trees have held off autumn. The mountains have found a way to hold onto summer. The landscape is covered in broccoli florets, making it just as supple as the clouds in the far-stretching sky. It’s beautiful, but there’s a small sense of disappointment. I’m not sure if Seoraksan will have what I’m looking for. I am here with other foreign English teachers, and we head down from our pension room to the lobby. The manager suggests a few options for hikes. We decide to go to Geumganggul Cave, approximately a 2,000-foot climb. The manager says there is a Buddhist Temple at the top.

Image courtesy of the author.

Throughout my childhood, I wanted to distance myself from the religion I was raised in. It was conspicuous enough that my family was the only immigrant family on the street. Did we have to be Buddhists, too? Did we need an additional marker of distinction? But living in an Asian country has piqued my curiosity about Buddhism. Even though I am not Korean, I want to connect to my Asian roots. After trying out and considering other religions throughout my young adulthood, I’ve settled back on my mom’s faith. I want to understand it the way she does. We run into the giant Buddha statue on the way. Despite his size, he is not an imposing presence. He sits cross-legged, his left hand is palm-face up and his right hand is gently draped over his right shin—a mudra showing his enlightenment. His eyes are slivers, but they’re not closed. There’s a slight smile on his lips.

***

Why did I need change so much? In Nevada, I was someone who put others’ needs and desires before mine, especially in my relationship. I had taken a leap of faith when I moved to Nevada — I left a stable job and friends to live with my boyfriend. Years into our long-distance affair, we knew one of us had to make the move. I decided it would be me. I justified it by convincing myself he was more established and successful where he was. So I moved. No job. No friends. No family. Just him. And just love to sustain me. The things I gave up left me empty, and the uncertainty of our future together left me insecure. Emptiness and insecurity fueled one another in an endless exchange. I wasn’t happy, and I realized it was because what I thought was my easy-going nature was actually complicity. I didn’t want to be that person anymore. When I finally admitted this to myself, I felt something urgent. One day, I was one-half of a nearly six-year partnership. The next day, I heard a voice screaming, This is not your life. Your life is somewhere else. Once I started listening to that voice, it became the gospel I followed faithfully. I embraced change with abandon. I would leave everything behind if I had to. And I did.

***

Just go, just go, just go. Go, go, go go. It’s what I say to myself when the trail becomes a series of narrow switchbacks. I know if I go slow, the hike will be twice as grueling. So I whisper this to myself until I get to a flat spot where I can rest. We have come to a long and intimidating red staircase. The first few steps are short, and the stairs are weirdly spaced. I can’t look out, even though I know it’s a beautiful view. I never know when my dormant fear of heights turns from being a minor annoyance to a crippling condition. So when I cross the stairs, I play it safe and focus on my bright mint green and neon Nikes.

Despite my tentative approach, my foot falls heavy on the cast-iron stairs. The staircase is cast against a canvas of jagged rock slabs. Directly underneath is just a long drop to the bottom. The staircase spills out onto a natural platform, where I can see how high I’ve climbed.

Seoraksan National Park, photo by Garycycles / CC BY.

“Do we have much farther until the temple?” I ask. “Or is this staircase going straight up to heaven?”

“I think it’s up there,” replies Kristin, one of the other women on the trip. She points to an even steeper staircase. I look up and see the mouth of the cave. I think about turning around. The next staircase looks like a ladder. I want to forget about how fast and horrific a drop from that height would be. Could there really be a temple up there? I have to find out. People suspend their fear of falling just to see it. For the moment, I have to forget my fear, too.

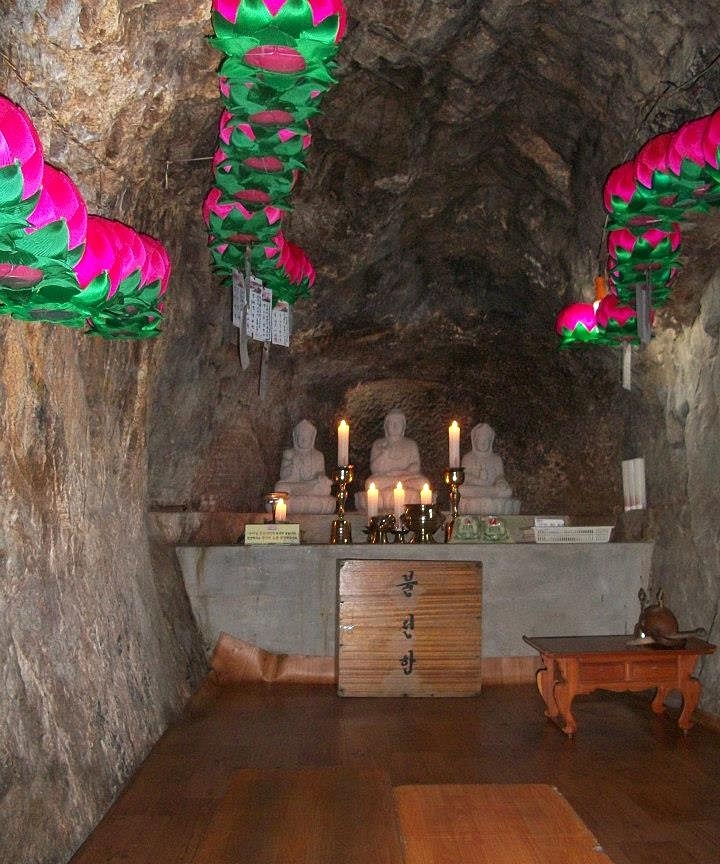

I grip the railing tightly with both hands. I make sure each stair is completely under me before I put my weight on my foot. I go slow and then finally, we reach the mouth of the cave. It is dark, so my eyes have to adjust. When they do, I see a shallow hole with three small white statues and five candles in front of them. There is faux wood adhesive flooring and two mats for praying. I look around, searching for something more. Three rows of pink prayer lanterns line the roof. There is a woman at a small stand selling trinkets and bracelets. Her cart can be folded like a wooden backpack. I imagine her putting it on her back and climbing those stairs every day.

Image courtesy of the author.

Winded and disappointed, I take a moment to catch my breath. A swift breeze falls over my bare arms. I walk into the cave, and see three small white statues. I kneel and search for sticks of incense, but there’s nothing here. I guess I’ll just have to pray without the incense. I press my fingers and palms together. I close my eyes. I say my grown-up prayer, different from the money or wealth or good-paying job I used to ask for when I was younger. Since learning more about Buddhism, I’ve held onto this tenet: Everything is temporary “Allow me to be more open, more patient, and more understanding. Help me accept change, no matter its forms.” My hands rock back and forth three times, and I open my eyes. When I turn around, I see the expansive Cheonbuldong Valley underneath me. Craggy rocks and mountains go until the horizon line. The radiant light at this time of day allows me to see the outline of every mountain edge. The blue sky and green trees make a sharp contrast. I can see why that woman makes her daily treacherous trek. This is what she gets to gaze out into every day.

I’m just a couple feet away from the edge. I let the sun warm my face. The Cheonbuldong Valley is so still that it’s like I’m looking out into a massive painting. The sharp angles of the mountains below are hidden by a canopy of thick trees. The few clouds in the sky are motionless, and the sunlight shines through them as if they were gossamer. Guemganggul Cave is where Buddhist monks used to retreat to for prayer and meditation. They found peace in the humble temple that resides in the middle of this mammoth rock. Although the cave is seen more by tourists than monks these days, that same peace can still be found. From this view, I am suddenly very aware of my place in the world, of how very insignificant I am in the midst of this valley. There’s a growing acceptance that comes with this peace and as I head back down the steep stairs, I feel an overwhelming comfort in my smallness.

Maggie Thach Morshed is a former award-winning sports journalist. She has an MFA from UC Riverside, Palm Desert. She is currently at work on a memoir about living and teaching in South Korea. Much of her writing revolves around the themes of immigration, identity, and assimilation.